The Lancet, alcohol and me

To share without moderation

Improperly cooked statistics are toxic (*)

You all know The Lancet, the highly respected British medical journal, and you have read this thrilling article, published on April 14, 2018, "Risk Thresholds for Alcohol Consumption : combined analysis of individual-participant data for 599,912 current drinkers in 83 prospective studies".

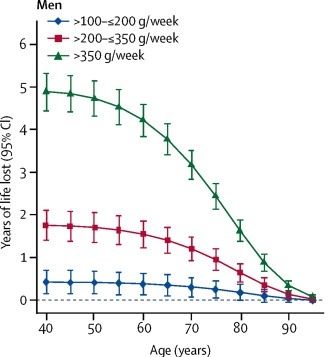

Being a conscientious drinker, I was particularly interested in the part of the study dealing with alcohol and lifespan. After boiling in big statistical cauldrons data collected from more than half a million drinkers from 19 high income countries, the study determines the years of life lost according to age and consumption, independently of the many other parameters affecting lifespan. I refer to the article published on April 14, 2018 and not the one of August 24, 2018. I was particularly struck by the following graphs :

These graphs indicate the number of years of life lost according to age and weekly consumption of alcohol for men and women. The calculation of this loss is done in reference to the group of very small drinkers: from 0 g up to 100 g of alcohol per week. Non-drinkers are not considered because they constitute a separate and non-homogeneous population. In France, in 2015, 13.6% of adults were non-drinkers.

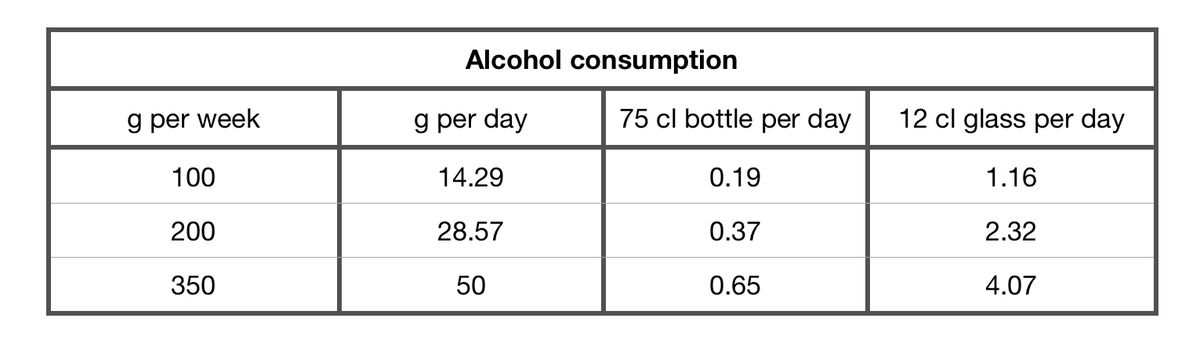

A bottle of wine of 75 cl at 13% contains 77 g of alcohol, this bottle contains between 6 and 7 glasses and a glass of 12 cl contains 12.3 g of alcohol. So then the consumption limits used in the study correspond to the following daily values.

I will now consider the results published by this respected journal as a good picture of my fellow drinkers and I will try to find where I stand in their company.

It is easy to see that the blue group (100 to 200 g per week) lives on average longer than the green group (+ 350 g per week). Another point, encouraging for the elderly, is that the number of years of life lost deceases as they grow older: they can reasonably consider increasing their consumption without excessive damage.

After these general comments, let’s consider my favourite case, myself. I am a 75-year-old man who drinks a bottle of wine a day, even more on special occasions and small peated malts from time to time. With a base consumption of 540 g per week, I am clearly in the green group. The Lancet article indicates that the average consumption in this group is 367 g per week. I am therefore in the upper part of my group and I lose at least 2 years and 4 months of life. If I move into the red group, a rather depressing idea with only half a bottle a day, I lose only 11 months, a gain of 17 months. Let's go further into the trial, in the blue group, with a quarter of a litre of wine a day: I lose only 2.8 months, a gain of more than 2 years of life compared to my current situation.

Let’s stop kidding

Most of us, even educated people including many medical doctors, will apply these graphs to individual cases as I did here. The meaning of some apparently simple statistics seems obvious to most of us. In fact, statistics is a very peculiar science and a proper analysis of its results necessitate a rigorous skill. A naive interpretation leads usually to stupid and dangerous conclusions.

The misuse of statistics by media, authorities and activists with unclear motives is a general and toxic practise mixing ignorance and perfidy. Both are present here to conclude that we must stop drinking.

Who is really concerned by this work?

Only the drinkers who will die from their alcoholism can possibly be afraid. A study published by the respected Gustave Roussy Institute indicates that in France in 2009 the number of deaths that can be charged to alcohol is 49,000 with 15,000 cancers, 12,000 cardiovascular diseases, 8,000 digestive diseases, 8,000 without pathological cause (road accidents, suicides, etc. ...), 3,000 mental disorders or behaviour disorders. Related to the 540,000 deaths recorded this year, the incidence is 9% (13% for men and 5% for women). It is very low compared to the 100% of people who died this year.

To answer this argument, authorities tell us that alcohol is a cause of avoidable mortality. It is difficult to establish the limits of this interesting concept. It can cover many activities, including sports. Yes, but sports is good for you. To this, I will answer that alcohol, too, is good, if you take some time to think of it.

Rational analysis of these graphs

It is necessary to keep in mind a fundamental point: the graphs show average values established for all drinkers. The average life loss in my group is 28 months but the individual results are spread around this mean value. Some may be 10 years higher and other 10 years lower. As an individual, I don’t know where I stand in my group.

I would be interesting to know how the results in my group are distributed around the 28 months average. If most of them stand between 26 and 30, then 28 months is a good indication for everybody in the group. Conversely, if the results stand between - 4 months and 60 months, the mean value is a very vague indication. The negative value in this example is not an error. As the overall effect of alcohol on an individual can be unfavourable or favourable, alcohol consumption may sometimes produce a benefice. Unfortunately, information on the spread of the results is missing.

All I can deduce for me is a vague feeling that it might be better if I drink slightly less, but I am not sure. Thus, these statistics gives only a general picture of a situation, a bit like a class photo in which you know nobody.

Maybe my doctor can draw more information from the Lancet paper. But concerning my case, he will use all he knows about me and probably advise me to slow down a bit. The day he tells me to keep on drinking according to my pleasure, I will be very worried. It will be because he is convinced that my cancer will take me under before alcohol.

Human longevity implies other parameters apart from alcohol: tobacco, too, has a bad reputation, as well as poverty, despair, stress and gruelling work. Genetic heritage also plays a role. Finally, the quality of social and emotional life as well as income level are important factors. It seems that even physical activity can be favourable. I don’t know how these closely associated parameters interact in my life and I don’t know whether alcohol is bad or good for me.

Toxic use of the graphs

So many institutions claim that their only goal is to protect us from the hazards of life: they really want to help us. I must say that the older I grow, the more I hate them.

You know that insurance companies are here to protect us from accidents and misfortunes. It is at least what they try to convince us. In fact, they have little effect on accidents and misfortunes. At most, they pay compensations to us or to our designated beneficiaries if we die. As people do not like evil birds, they avoid speaking of death, big infirmities, fires and other miseries of the same nature. Their communication does wonder to show us the smiling and happy people they have protected. Life is a difficult game to play but they don’t mention it.

Stronger than insurance companies, some institutions are here to reduce all the risks. They tell us that zero risk does not exist but they do their best to protect us from weather, terrorist attacks, accidents, diseases and of course ourselves. The supreme protectors in this domain are the governments. They don’t need to be soft to attract us. On the contrary, they use strong images to show the disasters they are fighting with determination, and up to three ministers can come on the scene of a small school bus crash, not speaking of a terrorist attack. We need to be frightened to understand.

But other self-proclaimed protectors also exist, grouped together in associations to fight against all the dangers. Their benevolence is often extremely toxic and the governments are usually eager to listen to them.

The use of the Lancet article is a perfect example of this process: try to scare us and promote measures for our alleged benefice. Let’s examine what appears to be a small detail. This kind of study is usually not available to the public. You must pay the publisher - Elsevier in this case - before accessing to it. Thanks to a special subsidy of the Medical Research Council free access has been allowed (**). This rings a bell when you think of it.

Before providing free access to this very technical literature, the Medical Research Council could have asked the authors to write a little presentation putting their results in perspective. This would have avoided the serious reading errors we found in most media. Unfortunately, they did not think of it.

All these benevolent people

So many institutions claim that their only goal is to protect us from the hazards of life: they really want to help us. I must say that the older I grow, the more I hate them.

You know that insurance companies are here to protect us from accidents and misfortunes. It is at least what they try to convince us. In fact, they have little effect on accidents and misfortunes. At most, they pay compensations to us or to our designated beneficiaries if we die. As people do not like evil birds, they avoid speaking of death, big infirmities, fires and other miseries of the same nature. Their communication does wonder to show us the smiling and happy people they have protected. Life is a difficult game to play but they don’t mention it.

Stronger than insurance companies, some institutions are here to reduce all the risks. They tell us that zero risk does not exist but they do their best to protect us from weather, terrorist attacks, accidents, diseases and of course ourselves. The supreme protectors in this domain are the governments. They don’t need to be soft to attract us. On the contrary, they use strong images to show the disasters they are fighting with determination, and up to three ministers can come on the scene of a small school bus crash, not speaking of a terrorist attack. We need to be frightened to understand.

But other self-proclaimed protectors also exist, grouped together in associations to fight against all the dangers. Their benevolence is often extremely toxic and the governments are usually eager to listen to them.

The use of the Lancet article is a perfect example of this process: try to scare us and promote measures for our alleged benefice. Let’s examine what appears to be a small detail. This kind of study is usually not available to the public. You must pay the publisher - Elsevier in this case - before accessing to it. Thanks to a special subsidy of the Medical Research Council free access has been allowed (**). This rings a bell when you think of it.

Before providing free access to this very technical literature, the Medical Research Council could have asked the authors to write a little presentation putting their results in perspective. This would have avoided the serious reading errors we found in most media. Unfortunately, they did not think of it.

Conclusions

A first conclusion says: "Our study shows that among current drinkers, the threshold for lowest risk of all-cause mortality was about 100 g per week", a good glass of wine a day. A very good piece of news! As soon as the paper was published, the orthodox guards started a counterattack. Only four months after the initial paper, this unsustainable truth was revealed: "Only a zero consumption of alcohol reduced to zero the risk of suffering the consequences of alcohol consumption". Only total abstinence will save us. And all the media started to sing in chorus this exceptional result. We are no longer in science but indeed in a toxic propaganda.

David Spiegelhalter, professor at the Statistical Laboratory of Cambridge University as the Winton Professor of the Public Understanding of Risk noted that the absence of a level of consumption ensuring a lower risk does not imply the necessity of abstinence. As an example, he noticed that this analysis can be applied to driving, but no government will consider banning driving.

The second conclusion is the following advice: "These data support adoption of lower limits of alcohol consumption than are recommended in most current guidelines". The way they reached this conclusion remains double Dutch to me. In fact, this conclusion appears to be just a gentle self-justification for a study funded by various public institutions. But it is not trivial; it brings grist to the mill of all the freedom shrinkers and comforts the bad practice of so many institutions entirely devoted to our welfare.

Hidden facts

In these times of paranoia, evocation of hidden facts cannot fail to generate interest. That's why I'm going to mention some small things. Living is dangerous, even taking a little walk around the corner. Talking about the risks associated with an activity is a truncated speech if we don’t mention the associated benefits. We need to permanently arbitrate between risks and benefits, whether we want to buy bread at the next-door bakery or climb a mountain. And we must not trust anyone for this arbitration. It is our freedom which is at stake, or at least what remains of it.

Last words

At the end of my very imperfect work, I want to return to my own case. I have decided to reduce my wine consumption. My liver is fine, but my old stomach tolerates less and less ordinary wine. I must drink better, but in reduced quantity because my pension decreases. It goes without saying that the reduction will be very progressive and carefully limited.

December 19, 2018

Gilles Muratet

Posted on my blog at http://www.ungraindesable.com/2018/12/the-lancet-alcohol-and-me.html

——-

(*) Based on an article written in french and posted on my blog at http://www.ungraindesable.com/the-lancet-le-vin-et-moi

(**) https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)30134-X/fulltext

Note: I have no conflict of interest with the wine making activity or related business such as wine trade. So I will gladly accept some very good bottles as a mark of recognition of the value of my work.